Life on the Research Icebreaker Nathaniel B. Palmer

/By Peter Sheehan and Linda Welzenbach

The Nathaniel B Palmer is, without a doubt, one of most amazing places I can say I call home. It is taking us places that even those of us who are “Old Antarctic Explorers” have never seen. The Palmer can manage Southern Ocean tempests (see blog…), dodges amazing icebergs, glides through sea ice, and is now charting new waters in front of Thwaites glacier.

The Nathaniel B. Palmer at the face of the Thwaites Glacier Ice Shelf. The ship’s close distance to the ice allows detailed mapping of the front and multibeam bathymetry. The angle of the echo sounder beam extends beneath the ice edge to see the seafloor a few meters under the shelf. I will talk about Thwaites Glacier itself in the next blog.

Twenty six people from more than 7 nations and scientific disciplines (from marine mammal biology, physical oceanography, glaciology to geology) are focused on Thwaites Glacier. Yet regardless of our collective focus, each of us experiences life on board in different ways.

With nearly a month on board, we have all settled into some measure of routine, most of which (and most everyone will agree) revolves around chow-time and the shiftwork that defines our science activities. Beyond that there is always something new to discover and yet may remind us of what it was like at the beginning, trying to find our way (and our sea legs) around the Research Vessel/Ice Breaker (RV/IB) Nathaniel B. Palmer…

The following account was written at the beginning of the cruise, with the hope there would be time to talk a little bit about life on the RV/IB Nathaniel B. Palmer. The early Hugin testing, the very rough seas and complex start to our cruise shifted that focus. As we are currently at Thwaites, but experiencing yet another tempest (blizzard conditions- sustained 35-40 knot winds gusting to 50) we thought this would be a good opportunity to provide a look at what living on board a research vessel is like.

In the Beginning…. By Peter Sheehan

So this is a big boat. Spread over six occupied decks, and with a vast underbelly of engine rooms and storage hangars built into the hull, the Palmer measures almost 100 m (300 ft) from one end to the other and has room enough for some 50 people. But what has surprised me most, even though, unusually, this cruise carries almost a full complement of scientists and crew, is how roomy things feel. Writing this blog in one of the many labs and work rooms that comprise the main deck, I have only one other person for company. People bustle up and down in the corridor – someone just waltzed past but by no means are we all sat on top of one another like inhabitants of a human beehive.

The E-lab is the nerve center and office space for all the science teams. Everyone in the E-lab looking excitedly at the Hugin AUV (see blog…) high resolution side-looking sonar of the seafloor surface in front of the Thwaites ice shelf.

I have been aboard the Nathaniel B Palmer, the ice-breaking research ship operated by the United States Antarctic Program, for almost two days now, yet there is scarcely a foray out of my cabin that does not involve a protracted mix-up over decks, corridors – or even which end of the ship is which. I just went for a coffee and ended up in a laundry room. To exacerbate my problems getting around, all of the corridors have the same green doors and the same green laminate flooring. It is this disorientating similarity that makes a laundry room look a lot like a mess hall – dining room, to you and me – to the unsuspecting junior scientist.

THOR coring PI Becky Totten Minzoni consults the map of the 01 deck to locate the room she and Linda will share.

The other thing that’s spiced up my first couple of days on the Palmer is the fact that everything has a silly name on a ship. The mess hall I’ve mentioned; the kitchen is actually the galley; bathrooms are called heads – go figure; and even words as ostensibly straightforward as front and back are, in fact, fore and aft respectively. The crew drop bandy (British to English translation is “ship speak”) these terms about with a breezy confidence, but to the uninitiated they add considerably to the brain fog – so don’t even think about asking for directions. I am assured that I shall know the Palmer like the back of my hand within another couple of days, but I am not convinced that people appreciate how heroically series I am when I say I have no sense of direction.

The mess hall is located near the bow the ship. Its outer walls are right next to the ice breaking going on, making conversations difficult to hear at times.

The silver diner-like atmosphere is quite comfortable, with each table providing at least 20 different sauces, condiments and spices to accommodate most palates.

One of the highlights of the Palmer is the fantastic array of baked goods, from handmade dinner rolls to a cinnamon “King cake” to start off the Mardi Gras season.

The room that I was most excited to find on my misadventures was the sauna. My friends are always delighted when I talk about going on a science “cruise” given that there is not a piña colada in sight – and, granted, this is a far cry from hopping about Greek Islands with David Hasselhoff or the last surviving Bee Gee. But we have had two weeks in one of the coldest parts of the world: and although I’m still waiting for a swimming pool and a suite of sun loungers I defy you to tell me that a sauna is anything other than a game changer.- P.S.

The sauna serves a dual purpose. While arguably a place to unwind from long days of the hard work that comes with maximizing the science, it also provides warmth to cold crew and scientists coming back from icy excursions or science-based deck work that can’t be accomplished in the labs.

News is posted on “The white boards”. Each day will list scheduled science activities, but may include training, lectures and even social activities.

The Palmer’s gym

The aft cargo hold not only holds two sets of propeller blades, but also a strapped down Ping-Pong table, a good way to manage stress through friendly competition and physical activity. Peter and Chef Julian battle it out during the Transit Tournament.

The heart of science on the Palmer is located on the main deck, which hosts 3 dry laboratories. Two are computational (the primary one is called the E-lab) and one is for processing THOR Cores. There is one laboratory dedicated for biology and chemistry activities and includes a walk-in refrigerator that holds all THOR’s core archives and samples.

Scientists on NBP1902 spend most of their time in the E-lab. The E-lab is the nerve center, meeting room, seafloor mapping, Hugin mission control, CTD data monitoring and workstations for all the participants. The E-lab is our office on the sea. When not working, most of us can be found on the bridge, perched some 60 feet above the water line offering a 360 degree view of the world around the ship. The bridge holds a certain serenity, even during the worst of conditions, where one feels at once safe yet in touch with the wildest world outside.

Sunset on the bridge

Science is conducted 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Everyone works 12 (and more) hours per shift to accomplish as much science as possible in the short window of a cruise. Weather delays, equipment adjustments and fixes, environmental constraints (mostly weather related, but they can include ice issues) can create “hurry up and wait” situations. While we are always prepared to act on a moment’s notice, the in-between times may be filled with literature reading, data processing or ‘easy to pick up and put down’ creative activities. The E-lab has a stash of guitars within easy access, and there is no lack of musician scientists who make use of them.

Guitar scientists! THOR scientist Ali Graham, NBP electronics technician Barry Bjork, TARSAN scientists Bastien Queste and Guilherme Bortolotto.

At the end of the day, it is the 20 ship’s hands- captain and mates, engineers, seaman, oilers, cooks and 10 science support team members, keep us safe, well fed and ensure the success our science activities. It is an understatement to say that we all appreciate the hard work they do on our behalf. Life on board ship is not just about the Nathanial B. Palmer, it’s about the people who make it the most amazing and one-of-a-kind experience of a lifetime.

Peter is a postdoctoral researcher with TARSAN hailing from the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom. Usually his field research takes place in the distant and warm Indian Ocean making observations of ocean currents and the fresh water that exchanges from the ocean into the air during the seasonal monsoons. Peter finds himself out of his element, you might say, in the icy reaches of Antarctica, but has taken to it well, helping to deploy the various TARSAN ocean instruments (including the CTD), creating visualizations of the ocean data as it arrives from the instruments, and providing hilarity through unending witty sarcasm to lighten the most mundane of activities.

Time lapse videos touring the ship

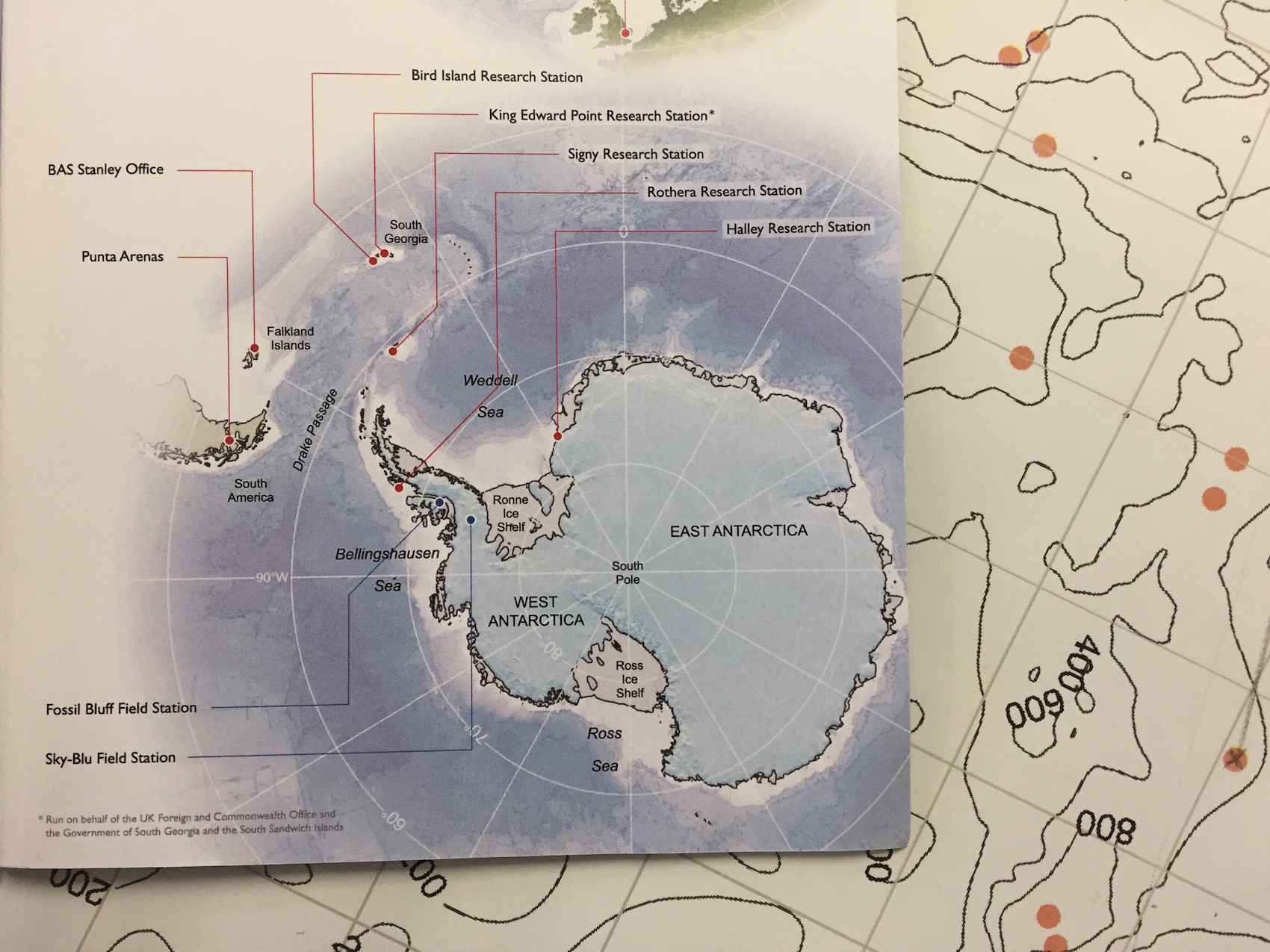

Sea Ice on the transit to Rothera station (by Peter Sheehan)